Is the Hardest Job in Education Selling Parents on San Francisco Public Schools?

The city’s public school enrollment has shrunk. Here’s how one district employee is fighting privatization, bad PR, segregation, and population loss.

Help fund stories like this.

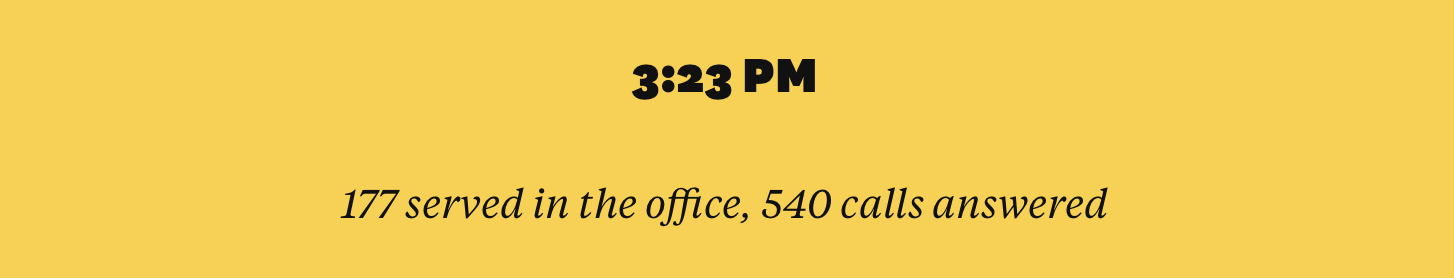

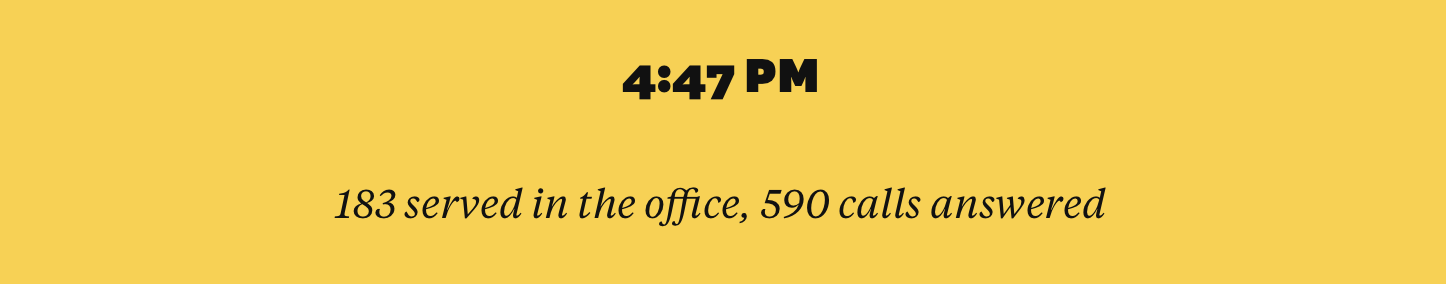

SAN FRANCISCO — It was two days before the start of the school year, and Lauren Koehler shrugged off her backpack and slid out of a maroon hoodie as she approached the blocky, concrete building that houses the San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) Enrollment Center. Koehler, the center’s 38-year-old executive director, usually focuses on strategy, but on this August day, she wanted to help her team — and the students it serves — get through the crush of office visits and calls that comes every year as families scramble at the last-minute for spots in the city’s schools. So when the center’s main phone line rang in her corner office, she answered.

“Good morning! Thank you for waiting,” Koehler chirped, her Texas accent audible around the edges. “How can I help you?”

On the line, Kelly Rodriguez explained that she wanted to move her 6-year-old from a private school to a public one for first grade, but only if a seat opened up at Sunset Elementary School, near their house on San Francisco’s predominantly white and Asian west side. Koehler told her the boy was fourth on the waitlist and that last year, three children got in.

“We will keep our fingers crossed,” Rodriguez said, sounding both resigned and hopeful.

Stanford professor Thomas Dee predicted this. Not this specific conversation, of course, but ones like it. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, public school enrollment in the United States had been , thanks to birth-rate declines and more restrictive immigration policies, but the decreases rarely exceeded half a percentage point. But Dee said, between fall 2019 and fall 2021, enrollment declined by 2.5 percent.

At the leading edge of this national trend is San Francisco. Public school enrollment there fell by 7.6 percent between 2019 and 2022, to 48,785 students. That drop left SFUSD at just over half the size it was in the 1960s, when it was one of the largest districts in the nation.

Declining enrollment can set off a downward spiral. For every student who leaves SFUSD, the district eventually receives approximately $14,650 less, using a conservative estimate of state funds for the 2022–23 school year. When considering all state and federal funds that year, the district stood to lose as much as $21,170 a child. Over time, less money translates to fewer adults to teach classes, clean bathrooms, help manage emotions and otherwise make a �徱���ٰ�������’s schools calm and effective. It also means fewer language programs, robotics labs and other enrichment opportunities that parents increasingly perceive as necessary. That, in turn, can lead to fewer families signing up — and even less money.

It’s why Koehler is trying everything she can to retain and recruit students in the face of myriad complications, from racism to game theory, and why educators and policymakers elsewhere ought to care whether she and her staff of 24 succeed.

Answering calls in August, Koehler had a plan — lots of little plans, really. And she hoped they’d move the needle on the �徱���ٰ�������’s enrollment numbers, to be released later in the year.

Koehler arrived at SFUSD in May 2020, which also happens to be when most believe the story of the �徱���ٰ�������’s hemorrhaging of students began. During Covid, the �徱���ٰ�������’s doors remained closed for more than a year. Sent home in March 2020, the youngest children went back part-time in April 2021; for of middle and high school students, schools didn’t reopen for 17 months, until August 2021. In contrast, most private schools in the city ramped up to full-time, in-person instruction for all grades over the fall of 2020.

It was the latest skirmish in a long-standing market competition in San Francisco — and the public schools lost. The �徱���ٰ�������’s pandemic-era enrollment decline was three times larger than the national one.

“My husband and I are both a product of a public school education, and it’s something we really wanted for our children,” said Rodriguez, the first caller. But her son ended up in private school, she explained, because “we didn’t want him sitting in front of a screen.” It was a conversation that has played out repeatedly for Koehler these past few years. But public schools staying remote for longer is not the whole story, not even close.

Remote schooling accounted for about a quarter of the enrollment decline nationally, Stanford’s Dee estimates. The bigger culprit, especially in San Francisco, is population loss. Even, the city the fewest 5-to-19-year-olds per capita of any US city, about 10 percent of the population, which is roughly half the.

Then, starting around the time Koehler arrived, fewer new kids came than usual and more residents moved to places like Florida and Texas. A recent Census found 89,000 K-12 students in San Francisco, about 93,000 in 2019. That decline represents more than half of SFUSD’s pandemic-era drop.

It’s difficult to pinpoint how many children migrated to private school in response to SFUSD’s doors’ staying closed, since many did, but at the same time, some private school students also moved away. But Dee’s research shows that private schooling increased by about 8 percent nationally. (Homeschooling numbers also grew, although the number of kids involved remains small.)

And these aren’t the only reasons Koehler’s task can seem Sisyphean.

“You guys should be able to find out how many spots are open!” a father sitting outside Koehler’s office said, frustrated after visiting the enrollment center once a week all summer.

Koehler nodded sympathetically and told him his son was sixth on the waitlist for Hoover Middle School and that three times that many got in last year.

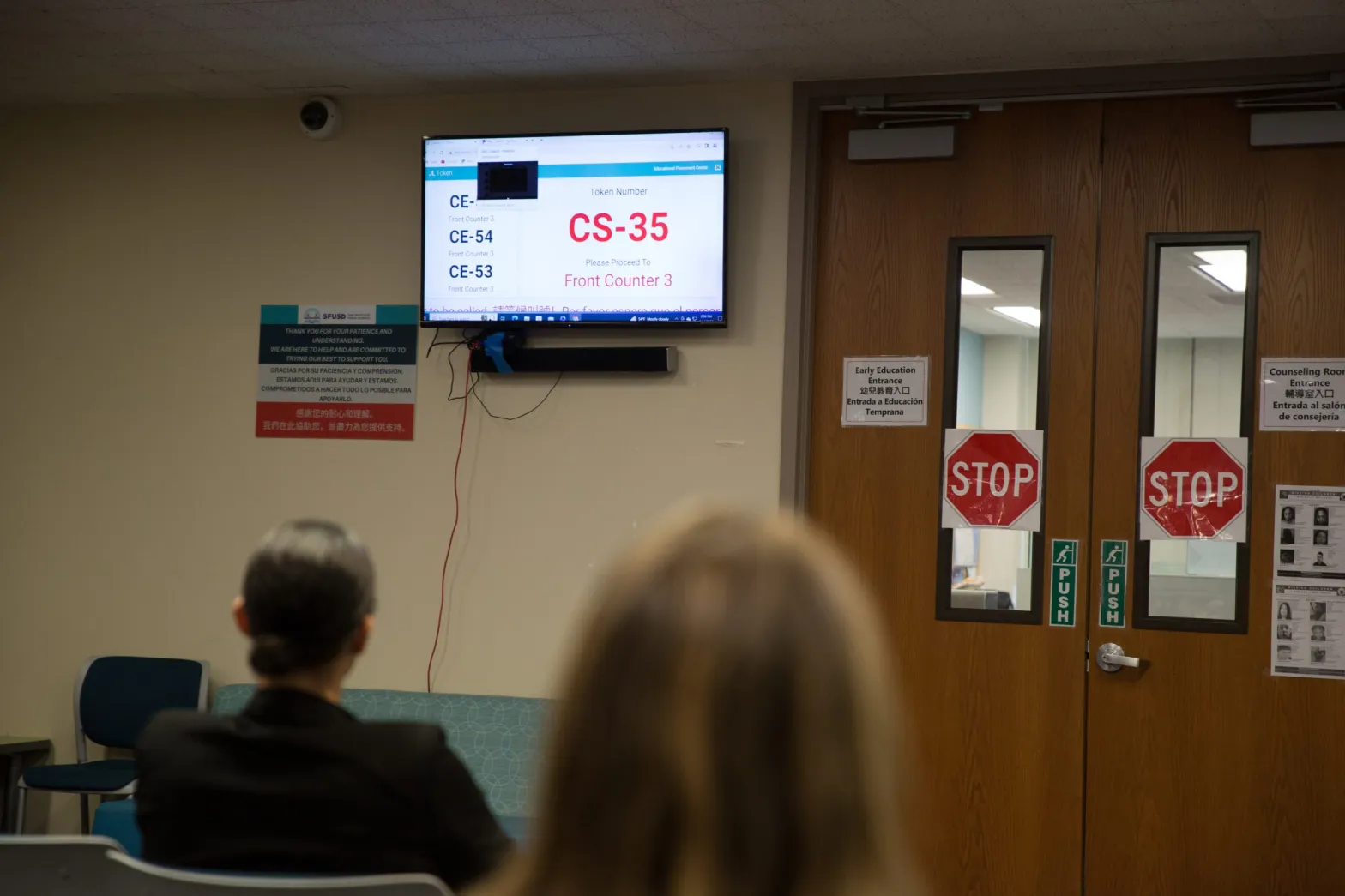

Since 2011, families have been able to apply to any of the city’s 72 public elementary schools, submitting a ranked list of choices. The same goes for middle and high school options. When demand exceeds seats, the enrollment center uses “tiebreakers,” mandated by the city’s elected school board, that try to keep siblings together, give students from marginalized communities a leg up, and let preschoolers stay at their school for kindergarten. After that, living near a school often confers priority. A randomized lottery for each school sorts out the rest, which leads to the entire system being referred to locally as “the lottery.”

Sixty percent of applicants got their first choice in the lottery’s “main round” in March 2023. Almost 90 percent were assigned to one of their listed schools. That makes for a lot of happy campers. It also makes for parents like the father with a wait-listed son, holding out for a better option.

Though she responded to him with unwavering calm, Koehler was frustrated too. She knew a seat would be available for his son, but state law prohibited her from letting the boy sit in it until an assigned student told the enrollment center they wouldn’t attend or failed to show up in the first week of school.

“I appreciate your patience,” she said, scrawling her cell number on a business card.

To avoid this bind, Koehler and her team have been experimenting with over-assigning kids, the way airlines overbook flights. New, too, is Koehler’s transparency about wait-list standing. In fact, at the beginning of August, every wait-listed family received an e-mail sharing its child’s standing, plus how many kids on the list got in last year. Koehler and her staff hope promising data will encourage parents to hang in there, while a disappointing forecast will open their minds to another school in SFUSD.

Overbooking and transparency represent incremental change. “I annoy some people on my team to no end by being like, ‘Well, I don’t know if we’re ready for this really large step, but let’s take a small step,’” Koehler said. “Let’s put as many irons in the fire as we can.”

Koehler’s next caller said, “The students are not getting their schedules until 24 hours before school starts, which is completely absurd!” Her voice fraying, the mother shared her suspicion that this was true only for kids coming from private middle schools, like her son. Koehler explained that the policy applied to all ninth graders, but still, she said, “I’m sure that’s stressful and annoying.”

Another caller had her heart set on Lincoln High School, down the block from the family’s home. But her son had been assigned to a school lower on the family’s list and an hour-long bus ride away. Koehler suggested several high schools that would have been a short detour on the woman’s way to work south of the city, but the mother began to cry. She had no interest in “Mission High or whatever,” even when Koehler pointed to Mission’s the highest University of California acceptance rate in SFUSD.

Family and friends are most influential in shaping people’s attitudes about schools, research specific to SFUSD shows. So if they’ve heard bad things, Koehler’s singing a school’s praises often does little to change their minds. Parents also turn to, which push families toward schools with relatively few Black and Hispanic students, like Lincoln, which currently scores a 7 on GreatSchools.org’s 1-10 scoring system, while Mission rates a 3.

As the mother on the phone grew increasingly distressed, Koehler responded simply, “I hear you.” And then, “I know this is really hard.”

She learned these lines from her therapist husband. Before they met, Koehler was an AmeriCorps teacher at a preschool serving kids in a high-poverty community. By her own admission, Koehler was “a totally hopeless teacher,” and she couldn’t stop thinking about “all these systems-level issues.” When her pre-K class toured potential kindergartens, she said, “The schools were just so different from each other.” She realized, “Where you are assigning kids — and what their resourcing level is — matters.”

After getting a master’s in public policy at Harvard, Koehler took a planning job with Jefferson Parish Public School System in New Orleans and then became a director of strategic projects with the KIPP charter school network in Houston. She moved to the Bay Area in 2018 to work for a different charter network, and that’s when she met the handsome, “uncommonly honest” school counselor. When she joined SFUSD in 2020, her husband struck out into private practice. “I feel like I get training every day,” quipped Koehler of his reassurances at home.

Now, she has her staff role-play parent counseling sessions, practicing skills picked up during trainings on de-escalation, listening so that people feel heard, and other forms of “nonviolent communication.” They try to make families feel understood and give them a sense of autonomy and control.

Often, they succeed. Often, they fail.

When phone lines quieted, Koehler began to call parents from the waiting area back to a sunny conference room featuring two massive city maps dotted by district schools.

The first family told her they live in Mission Bay, a rapidly redeveloping area where a new elementary school isn’t until 2025. They were excited about a school one neighborhood over, until they tested the two-bus commute with a preschooler. Then they realized that the city’s recently opened underground transit line goes straight from their home to Gordon J. Lau Elementary. Koehler wasn’t optimistic about there being openings; it’s a popular school.

When the computer revealed one last spot, she squealed à la Margot Robbie’s Barbie, “You are having the luckiest day!”

But the next parent, Kristina Kunz, was not as lucky. “My daughter was at Francisco during the stabbing last year,” she told Koehler. The sixth grader didn’t witness the March 2023 event, but when the school was evacuated, she thought she was about to die in a mass shooting. Once home, she refused to go back. Kunz told Koehler the family would have left the district, but they’d already been paying Catholic school tuition for her brother after he’d felt threatened at another middle school a few years earlier. “That was literally the only option,” Kunz said, “and we absolutely can’t afford it this year.”

Koehler read Kunz the list of middle schools with openings, all in the city’s southeast, which has a higher percentage of Black and Hispanic residents than other parts of the city. “Huh uh,” Kunz said, “none of those.” She’d take her chances waiting for a spot to open at Hoover on the west side.

The next parent, a woman who’d recently sent a vitriolic e-mail to the superintendent, said, “There’s no seats open in middle schools.” When Koehler rattled off the schools in the southeast that still had openings, the mother shrugged, as if those didn’t count.

Koehler closed her eyes and quickly inhaled. What she didn’t get into, but was perpetually on her mind, is what she’d read in“,” by Rand Quinn, a political sociologist at the University of Pennsylvania.

San Francisco segregated its schools from its earliest days. In 1870, students with Asian ancestry were officially allowed in any school, but often weren’t welcome in them, leaving most Asian American kids to learn in community-run and missionary schools. In 1875, the district declared schools open to Black students too, but nearly a century later, in 1965, 17 schools were more than 90 percent white and nine were more than 90 percent Black. A large system of parochial schools thrived alongside a handful of nonreligious, exclusively white private schools.

Public school desegregation efforts began in earnest in 1969 with the Equality/Quality plan, which, though modest, involved busing some students from predominantly white neighborhoods. An uproar followed, and the district, which had more than 90,000 students at its 1960s zenith, saw its numbers drop by more than 8,000 students between the spring and fall of 1970 as families fled integration. Over the next dozen years, SFUSD’s rolls decreased by more than 35,000, owing to white flight and also to the last of the baby boomers aging out and drastic public school funding cuts in the wake of a 1978 state proposition that largely froze the property tax base.

After 1980, enrollment bounced back a little, but then for years it plateaued at roughly 52,000 students. During the 1965–66 school year, more than 45 percent of the �徱���ٰ�������’s students were white. By 1977, just over 14 percent were. Today, that number is just under 14 percent. All of which is to say, when white families left in droves, they never really came back.

There have been about half a dozen similar initiatives since Equality/Quality — with names like Horseshoe and Educational Redesign — and each time, some west-side parents mounted opposition. Quinn quoted a former superintendent, Arlene Ackerman, who said at the outset of one of those “neighborhood schools” campaigns in the early 2000s: “They’ve said racist things I hadn’t heard since the late ’60s…talking about ‘in that neighborhood, my child might be raped!’”

It’s not just white families who object to their kids being educated alongside a significant number of Black children, said longtime Board of Education Commissioner Mark Sanchez. “You see that in the Latinx population and Asian population as well.”

In nearby Marin County, home to some of the nation’s most affluent suburbs, private schools opened one after the other in the 1970s. At least another 10 independent schools popped up in San Francisco proper, stealing market share from both SFUSD and the city’s parochial sector and pushing overall private school enrollment for the first time. Today, approximately 25 percent of San Francisco’s school-aged children attend private school, compared to 8 percent of California and similar shares in many large cities. A November San Francisco Chronicle found that at least three independent schools have applied for permits to expand or renovate their campuses in order to make room for more students. At one private school, enrollment is projected to more than double.

When Americans think of , they think of the South, said Sanchez, but San Francisco has long had its own. In part because the city didn’t offer quality schooling to children of color. “You’ll see a lot of second-, third-, fourth-generation Latinos that will just only put their kids in Catholic school.”

These personal decisions have a ripple effect beyond decreasing SFUSD’s budget. Research that advantaged, white families’ turning away from public schools sends a signal to others about their quality. Other studies reveal that when private schools are an option, recent movers to gentrifying neighborhoods more likely to opt out of public schools. And it is well-established that segregated environments breed people who seek comfort in segregated environments.

“It’s kind of a chicken-and-the-egg thing,” Sanchez said: Private schools are there in part because of racial fear, and racial fear is perpetuated in part because private schools are there.

In 2015, in the southeast part of the city, SFUSD opened Willie Brown Middle School, that includes a wellness center, a library, a kitchen, a performing arts space, a computer lab, a maker space, a biotech lab, a health center, and a rainwater garden, in addition to light-filled classrooms. With small class sizes, bamboo cabinets, few staff vacancies, and furniture outfitted with wheels, it could easily be a private school.

But Willie Brown remained under-enrolled, year after year, even after the school board passed a policy giving its graduates preference for Lowell High School, known as the “crown jewel” of SFUSD. Last year, enrollment jumped when Koehler’s Enrollment Center overbooked the school in the first round, parents decided to give it a shot, and kids ended up happy. About 20 percent of the student body is now white, yet still, spots remained open two days before the start of school this past fall.

To some observers, Willie Brown is just the latest iteration of a failed “if you build it, they will come” narrative in San Francisco. In the second half of the 1970s, the district created new programs and “alternative schools,” akin to other cities’ magnet schools, to attract back families that had fled. Later, Superintendent Ackerman promised a flood of investment in schools in the southeast, including new language programs. There was a small effect on enrollment, Quinn said, but only on the margins.

So when the parent said, “There’s no seats open in middle schools,” Koehler understood that lots of factors influence which schools work for a family and which don’t. But there was also an echo of 1960s anti-integration parent groups.

“I’m sorry,” she replied, “I know this is really stressful.”

A 17-year-old newcomer to the US entered the Enrollment Center and sat across the conference room table from Koehler. She asked when he’d arrived in San Francisco.

���dz����Բ���.”

“Ayer?” Koehler asked. (Yesterday?)

“No, domingo pasado.” (Last Sunday.)

In New York City and other large cities, an increase in asylum-seeking families with stopping public school enrollment declines. Migrant children to San Francisco too, and Koehler’s team has tried to reduce the they and other families face when trying to enroll.

But Koehler would need to meet many more kids like this one to stave off school closures.

She’d also need charter school enrollment to stop increasing.

The next parent, also a recent immigrant, stepped into the conference room with a stack of papers issued by the Peruvian government and the conviction that her son needed to be placed in a different grade than the one specified by his age. She made it clear to Koehler that the family would jump at the first appropriate placement offer: SFUSD’s or at Thomas Edison Charter Academy. Koehler scrambled to get the boy assessed and recategorized.

Charter schools were first authorized in San Francisco in the 1990s. Though their share of the education market is smaller here than in places like New Orleans, charter enrollment has, with new schools often inhabiting the buildings of schools SFUSD had to close. Now, approximately 7,000 students attend charter schools rather than district ones.

On August 30, 2023, SFUSD families received an e-mail from the superintendent saying, “We are going to make some tough decisions in the coming months and all the options are on the table.”

Each time a student leaves the district, SFUSD has less money to operate that student’s old school. But the heating bill does not go down. The teacher must be paid the same amount. A class of 21 first graders — or even a class of eight — is no cheaper than a class of 22.

It stands to reason that closing under-enrolled schools and reassigning their students and the funds that go with them to different schools, as many districts across the country are to do, should produce better educational outcomes for all. But it often doesn’t, as experiences in , and illustrate. Sally A. Nuamah, a professor at Northwestern University, school closures as “reactive” and urged policymakers to focus instead on the root causes of declining enrollment, like the lack of affordable housing that drives families out of cities.

Koehler can control those things about as readily as she can dig a new train tunnel or decrease school-shooting fear. But she might be able to improve the �徱���ٰ�������’s reputation.

Her team started by modernizing marketing efforts, like going digital with preschool outreach, producing a video about each school, and rebooting the annual Enrollment Fair, a day when principals and PTA presidents sit behind more than 100 folding tables. Parents used to push strollers through the throngs to grab a handout and snippet of conversation; now, schools play videos and offer up QR codes too.

For two years, SFUSD has also worked with digital marketing companies. One “positive impression campaign” included social media posts pushed out by the San Francisco Public Library and the Department of Children, Youth, and Their Families. Images feature photos of smiling students alongside the names of the SFUSD schools and colleges they attended: For example, “Jazmine – Flynn Elementary School – Buena Vista Horace Mann K-8 – O’Connell High School – Stanford University.” In addition to online ads, the district has purchased radio spots and light-pole ads. It’s mailed postcards.

Koehler would like to increase the current outlay of about $10,000 a year, but it’s hard to spend on recruitment when instruction remains underfunded, even if increased enrollment would more than offset the cost. Especially since, at some point, marketing becomes futile. With a finite number of kids in the city, initiatives to increase market share become “robbing Peter to pay Paul,” Dee likes to say. (Private school-board members and admissions directors in San Francisco are also expressing alarm at population declines.)

And in San Francisco, any PR campaign contends with two major sources of bad PR: the press and parents. Koehler understands why journalists report on what’s in SFUSD: It’s their job. But she sees loads of negative headlines and very few accounts of the many things that are going right. Readers are left with the impression that private schools in the city are objectively better at serving students, which just isn’t true.

Some parents have left SFUSD or refused to enroll their kids because of substantive complaints, like with the �徱���ٰ�������’s decision not to offer Algebra I in eighth grade (starting in 2014). There is also some real scarcity in the process, as in Rodriguez’s case: There simply isn’t enough room on Sunset’s small campus for everyone who wants to be there. And individual families have unresolvable logistical constraints, and in very rare cases, truly legitimate safety concerns. But a lot of it has to do with timing — and fear.

When David, a father of two, rang the Enrollment Center, it was with the air of a man who just wanted to do the right thing.

After touring SFUSD’s George Peabody Elementary, David and his wife decided the school would be a great fit for their incoming kindergartener. There was something special about it, and they wanted her to learn in a diverse setting.

But they also wanted a backup plan, having heard of the lottery’s vagaries. “We had two number-one choices,” he said: Peabody and a Jewish private school. They applied to both. In March, their daughter was offered a spot at the private school — and one at a different SFUSD school they liked less. “If we got into Peabody in the first round, we would have gone to Peabody,” said David, who asked that his full name be withheld to protect his privacy. Instead, they signed a contract with the private school. “We put our daughter on the waitlist” for Peabody, he said, “and then kind of forgot about it.”

When the family got an e-mail offering a spot, on the Saturday before school started, they were excited enough to click “accept,” even though they would have lost their private school deposit. Then they learned that Peabody’s after-school program was full. “There was just no way that we could have made it happen without aftercare,” David said. So he called the Enrollment Center to offer the spot to another family.

Hearing David’s story, Koehler sighed. If she had been able to place his child at Peabody in the first round, aftercare would have been available there, but in August the only programs with openings were located offsite. Because that didn’t work for David’s family, Koehler was left with a seat sitting open at a high-demand school.

Private schools can require open houses, interviews, and a tuition deposit to help screen out all but the most interested families and reveal information about their likelihood of accepting an offer. But SFUSD has tried to do away with hurdles like that, since they disadvantage the already disadvantaged. With no way of gauging intention to attend, Koehler has to hold seats from March until August for thousands of students who ultimately won’t use them. And she can’t just overbook aggressively, because there are always outliers. This year, one of the city’s biggest middle schools saw every single child who was assigned in March, save one, show up in August. Private schools can more easily absorb extra kids if they overdo it with admissions a little, but Koehler risks a massive fiscal error under the �徱���ٰ�������’s union contract. And overbooking risks leaving other SFUSD schools under-enrolled, something single-campus private schools don’t have to worry about.

It leaves SFUSD an unpredictable mess able to enroll fewer families than it otherwise would. And because the process is a mess, more families apply to multiple systems to hedge their bets and end up holding on to multiple seats, making it all more of a mess.

But change is coming. In 2018, the school board a resolution to eventually overhaul SFUSD’s school assignment system. Starting in 2026, citywide elementary school choice will be replaced by choice within zones tied to students’ addresses. The task of sorting out the details has fallen to Koehler’s team, along with a group at Stanford co-led by Irene Lo, a professor in the school of engineering who has been trained to design and optimize “matching” markets like this one.

If Lo could start anywhere, she’d centralize the application process so that families would rank their true preferences: public, private, and charter. One algorithm could then assign the vast majority of seats in a single pass, largely eliminating delays like the one David’s family experienced. But private schools stand to lose ground by agreeing to that, and many public school supporters would argue that this condones and uplifts private and charter schools. So instead of centralization, Lo will start with prediction.

She’ll use AI and other modern modeling tools to anticipate what parents will like. Then there’s “strategy-proofing,” a term from game theory. Essentially, it means trying to set up a system that incentivizes parents to be truthful. Over the decades, families have taken advantage of loopholes allowing students to attend a different school than the one designated by their address. And not just a few families. In the late 1990s, it was more than half. To gain an advantage, they’ve also lied about their student’s ethnicity, “race-neutral diversity factors” such as mother’s education level, and their zip code. Any way each system could be gamed, it was gamed.

Lo said the new six or seven zones will be drawn so each comes close to reflecting the �徱���ٰ�������’s average socioeconomic status. Layered on top of that will be “” at each school, basically set-asides giving lower-income students first dibs on some seats to make sure diverse zones don’t segregate into schools with wealthier students and others with concentrated poverty. City blocks will be used as a proxy for students’ level of disadvantage.

It all sounds great. It also all sounds familiar. In the early 1970s, Horseshoe featured seven zones and assignment to schools so as to create racial balance. Educational Redesign relied on quotas to make sure no ethnic group exceeded 45 percent. The current lottery uses “microneighborhoods” to capture disadvantage.

What makes Koehler and Lo think the outcome could be different this time?

Lo admitted that they’re trying “another way of putting together the same ingredients.” It’s still guesswork, but with her cutting-edge tools it should be more accurate than the guesswork of the past. And while parents still won’t have complete predictability, they’ll have more than before.

“I understand this is really difficult,” Koehler said to the last parent of the day.

With the waiting room empty and back offices quiet, Koehler approached each member of her staff: “Go home, because I know this is going to be a really long week.”

It’s likely to be a very long year—and decade—for the enrollment center.

San Francisco was 40 percent white as of the last Census, but only 13.8 percent of its public school enrollment was. Even if Lo works the unprecedented miracle of getting schools to reflect the �徱���ٰ�������’s diversity, there is no hope that they will reflect the �����ٲ�’s&�Բ�����;without a major change in the way parents have behaved for decades. The data is clear: Without a critical mass of white students in a school, a significant number of parents won’t consider it.

Still, many families are choosing SFUSD, including some of those Koehler talked to in August. Kunz’s daughter got into Hoover off the waiting list. A few months into the school year, her mother said, she is thriving. Her older brother, the one who was pulled out of public middle school, chose SFUSD’s Ruth Asawa School of the Arts over a well-regarded Catholic high school.

Rodriguez, the mother who wanted to send her first grader to Sunset, learned a few days after her call with Koehler that everyone assigned had shown up, and her son wouldn’t be offered a spot. But Koehler’s team had another suggestion near the family’s home: Jefferson Elementary School. Rodriguez almost rejected it in favor of private school, but she’s relieved she didn’t.

“The community’s been very, very welcoming,” she said in October. “His teacher’s wonderful; she has almost 20 years of experience. It has a beautiful garden. The principal is really involved.” A few months later things were still going well: “Jefferson is just fantastic,” she said in December: “We’ve been really, really pleased.”

But Rodriguez said she’s still “recovering” from the enrollment process. “I also worry about the future of it, as we hear potential school closures, budget deficits,” she said. The family is considering selling their house, in favor of a place somewhere else in the Bay Area “where there aren’t so many of the issues that SFUSD is running into.”

In October, David said he and his wife wouldn’t necessarily send their second child to the Jewish private school: “I think we probably will look at Peabody again.” And if that happened, he said, they may even move their oldest over to SFUSD. But by December, his outlook was different. David said his family has been very happy with the private school experience.

Koehler knew about each of these outcomes and thousands more like them, and she hoped they would amount to a turned tide, with enrollment starting to creep up rather than down.

This fall, she and her team learned of SFUSD’s preliminary numbers: Enrollment increased from 48,785 to 49,143. That said, hundreds of those kids are 4-year-olds, sitting in “transitional kindergarten” spots newly added to a statewide specialized pre-K program. In essence, enrollment had flatlined.

Koehler felt nonetheless undaunted. The stable numbers mean “that our outreach is working,” she said. “We are not losing people at the rate that we otherwise might.”

And not all of her plans, her incremental tinkering, have come to fruition yet. “One of my random dreams is that we could do aftercare at the same time as we do enrollment,” she said. She also pointed to SFUSD’s efforts to realign program offerings with what parents want most, spread more success stories, better compensate teachers, and get a bond measure on an upcoming ballot. For the 2025–26 application cycle, her team would like to automatically assign families to multiple waiting lists, “which we hope will make at least the process seem less cumbersome and frightening,” she said. Add in Lo’s changes, Koehler said, and “we’ll draw people back who right now are frustrated by our process.”

“I have a sense that the future will be positive.”

This story about was produced by , a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the .

Help fund stories like this.

;)