Gaps Widening Between Indiana’s Highest- and Lowest-Performing Students

Aldeman: Until 2015, the state's fourth-graders needing the most help in reading made the greatest gains. But then, the bottom fell out

Help fund stories like this.

The exact date varies across grades and subjects, but Indiana’s student achievement scores peaked about a decade ago and have been falling since.

The decline started well before COVID-19 and has not affected students evenly. Perhaps not surprisingly, Indiana’s lowest-performing youngsters have suffered the largest losses.

This wasn’t always the case. In the early 2000s, the state’s achievement scores were rising, and those gains were broadly shared across student groups. In a recent project for The 74 Million, I called this “a tale of two eras.”

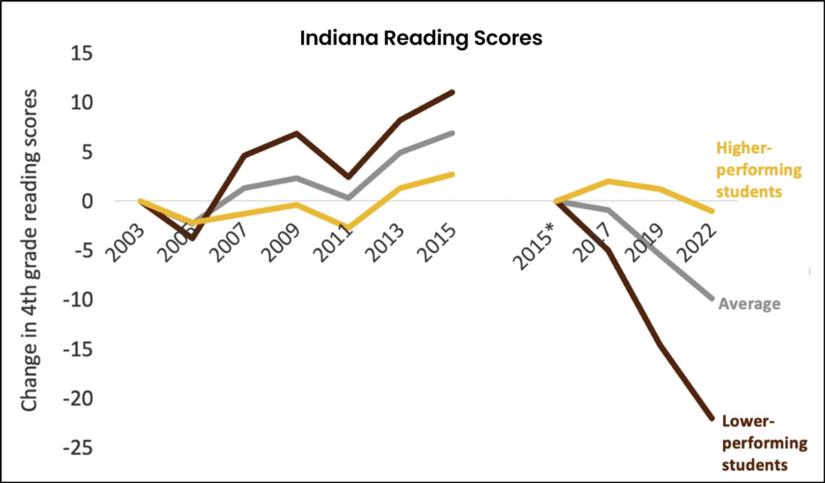

The graph below shows the Indiana story visually. It shows fourth-grade reading scores, broken out by student group. The statewide average is in gray, the highest-performing 10% of students are in yellow and the bottom 10% are in red.

The left side of the graph shows that average scores went up by 7 points from 2003 to 2015, led by an 11 point gain among the lowest-performing students (roughly equivalent to about one grade-level’s worth of gains).

But since then, the bottom has fallen out from under Indiana’s reading performance. While top performers have suffered a 1-point drop and the statewide average has fallen 10 points, the scores of the lowest-performing students have fallen 22 points.

What happened to cause this sudden reversal?

It’s tempting to jump to quick conclusions — Was it the Common Core? Is it the increased use of cell phones and other technology? But any good explanation should align with the exact timing and magnitude of the declines.

COVID-19 certainly exacerbated these trends, but they also pre-date the pandemic, so the story neither starts nor ends there.

It’s also not just an Indiana problem; achievement gaps are growing all across the country. As I noted in my original piece, “49 of 50 states, the District of Columbia and 17 out of 20 of the large cities that participated in NAEP” — the Nation’s Report Card — “saw a widening of their achievement gap over the last decade.”

Many readers have posited that the shift to the Common Core state standards was to blame. The timing does fit, but it doesn’t explain why the same patterns are playing out even in states that never adopted the Common Core, and in subjects like history and civics that weren’t covered by the standards.

It also can’t be money or teachers. In Indiana, for example, was more or less flat, in inflation-adjusted terms, while achievement was rising, and then spending started to rise around the same time achievement scores started to fall. Teacher staffing levels have also been rising over this period. Indiana schools went from having 17.4 students for every teacher a decade ago down to 15.8 as of the most recent data.

What about technology and social media? This one’s harder to disprove. As psychologist Jean Twenge has , the rise in smartphone usage aligns pretty closely with a decline in teen mental health and in-person social activities. It would make sense that the same trends are affecting academic achievement.

And yet, the technology argument has some flaws. For one, it doesn’t explain why achievement gaps are growing in the U.S. than in other developed countries. Two, the achievement declines in the U.S. are not limited to teenagers; they have been just as large among younger students who presumably have less access to phones and other technology. And three, it’s not clear why phones or social media would affect the lower-performing students but would not cause similar harms at the top.

But something must have happened about a decade ago to change the trajectory of student performance. In my original piece for The 74, I argue that the weakening of school accountability pressures after the No Child Left Behind Act was passed is responsible for a large portion of the drop. The timing of the change fits with the patterns both nationally and in Indiana. It also explains the growing achievement gaps. After state and district policymakers stopped focusing on the performance of kids at the bottom, their scores started to decline.

Regardless of which of these theories offers the best explanation, or whether it’s a combination of several, the data point to an alarming increase in achievement gaps in Indiana schools. It’s not just an Indiana problem, but the state’s policymakers will need to reverse these trends if they want to get achievement back on track.

Help fund stories like this.

;)